- Home

- Jo Glanville

Qissat Page 2

Qissat Read online

Page 2

2. Salma Khadra Jayyusi, Modern Arabic Fiction, New York, 2005, pp. 2930.

3. Therese Saliba, ‘A Country Beyond Reach’: Liana Badr’s ‘Writings of the Palestinian Diaspora’, in Intersections – Gender, Nation and Community in Arab Women’s Novels, eds. Lisa Suhei Majaj, Paula W. Sunderman and Therese Saliba, New York, 2002, pp. 132—61.

4. Bouthaina Shabaan, Both Right and Left Handed: Arab Women Talk about their Lives, London, 1988, p. 164.

Glossary

Abaya

gown which covers the body from neck to foot, worn by women in some parts of the Muslim world

Ammo

uncle

Arguileh

water-filtered smoking pipe

Dish dasha

traditional Arab robe (usually white) worn by men in the Arab world, particularly in the Gulf region

Fateha

opening chapter of the Quran

Fedayeen

freedom fighters

Hashem

God (Hebrew)

Hebron

West Bank town, where Israeli settlers live in the midst of the Palestinian majority population. It was the first town to be occupied by settlers after the Six Day War

Kaffik

high five

Kiryat Arba

Israeli settlement outside Hebron

Kuffiyeh

Palestinian scarf

Laysh

why

Ma zeh?

what’s this? (Hebrew)

Mabrouk

congratulations (Alf mabrouk a thousand congratulations)

Muqata’a

headquarters of the late Yasser Arafat in Ramallah

Purim

a Jewish festival, celebrated in a fancy dress carnival

Qais and Laila

the Romeo and Juliet of the Muslim world. Qais was driven mad by his love for Laila

Qalandia

Israeli checkpoint between Jerusalem and Ramallah

Shaheed

martyr

Shish barak

meat dumplings in yoghurt sauce

Souk

market

Sura

chapter in the Quran

Tawoule

backgammon

UNWRA

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, set up in 1949

Ya habibi

darling

Yia Yia

grandmother (Greek)

RANDA JARRAR

Barefoot Bridge

We’re on our way to Palestine, which Baba calls the bank – el daffa – to bury my Baba’s baba.

We have to fly to Jordan, and then drive to this daffa and cross a bridge. On the airplane I take out a map from the pocket in the seat in front of me, and on it Palestine is the country stuck to Egypt, so I ask Baba, ‘Why can’t we just drive there, or take a plane straight there?’ He tells me to be quiet and fasten my seat belt before the stewardess comes and kicks me off the plane. I remember that his Baba died and I should really be quiet. I want to hold his finger like the times we walked along the beach next to our apartment, the mud squishing underneath our sandals, my hand wrapped around his hairy finger. When the plane is in the sky, my ears feel like there’s a person inside my head pulling at them with a string. Gamal must feel this way too because he’s crying and throwing a fit.

In Jordan we take a taxi from the airport to the border. Baba sits next to the driver and looks straight ahead. I look all around me, at the rocks sticking out of the mountains that fly past us and the sand and the green trees lining the road. We go down a mountain and my ears finally pop. I feel like we’re on a roller-coaster, except we have windows.

I ask Mama for some paper and a pen, and she fishes them out of her bag. I’d like to draw what I see: the leather in the taxi, the cucumber sandwich my brother half-ate, Baba’s stubble, the dried skin around his eyes, Mama’s lipstick-lined mouth, her face, the face of the rocks outside, the wind whipping in through the window. I realise I can’t draw all these things, so I make a list of them. I don’t write numbers or anything, just list the things I’d like to record. After I’m done, I give Mama the sheet of paper, and she folds it in half without looking at it. Now I wish the wind would whisk the list I made and place it in Baba’s lap. Then he’d open it up and read it, and he’d feel better. Mama brings out a brush from her giant purse, which holds five years’ worth of receipts and eyeliners, and she brushes my hair impatiently. I want to say, ‘Ouch! It’s not my fault Baba’s baba died,’ but I don’t. Mama’s coral lips twitch as she brushes. I want to make her lips transform into a smile. I’ll write funny lists for her. The taxi goes all the way down the mountain, the wind rustling through the glass and whipping through my hair and messing it up again.

The car slows down and everyone inside it seems nervous. I look ahead and see yellow and black stripes on something that looks like a gate, and there’s a soldier there dressed in green. My father gives him papers and the man lets us out. We sit with several other families on benches by the road. Mama and Baba don’t talk, and I just look at the soldier and his shiny rifle. We sit for a long time, then a bus pulls up next to us, and we are allowed to get on.

The bodies on the bus sway back and forth, and from where I’m sitting I can barely see the people’s faces. Their bodies look like the dresses and T-shirts I saw a few days ago hanging up on wires at the souk. Two women start talking about what village they’re from, and then they smile because they are distant relatives. The driver stops the bus at another yellow and black gate and steps out for a moment. I follow him with my eyes, and watch him get a cigarette from the soldier who is coming up the steps. The soldier inspects all our passports with a cigarette dangling out of his mouth. He never takes it off his lips. I think this is a neat trick, but I’m worried about the long piece of ash hanging from it.

When the soldier’s done looking at papers, the bus driver gets back into his seat and drives again. We approach a bridge and the driver tells us we can get off. I ask Baba if this is the bridge and he nods his head and pats my shoulder.

Where we get off, there are many soldiers, boy ones and girl ones, standing outside a grey building. I walk past a girl soldier and admire her, her long curly hair tied up in a ponytail. Inside, we stand in a line with our luggage. After maybe an hour they check our bags, dumping their contents onto the wooden counters, and ask us where we live. Baba answers them and they zip up the bags and keep them, telling us to sit down and await inspection. I ask Baba how long all this will take, and he says, ‘All day,’ and looks over at the soldier. It seems like he and the soldier are talking, but they’re not saying a word. I go to Mama and she lets me take Gamal from her so she can rest. He is heavy and I can feel him farting through his underwear.

After a while Mama, my brother, and I are separated from Baba. We have to go to an area off to the side of the building and take our shoes off. There are many other girls there, and they have their shoes off as well. There are women in pretty dresses, women in jeans, women in veils, women in short skirts, women in traditional dresses with gold bracelets lining their arms and blue tattoos on their chins, women with big bug-eye sunglasses and big purple tinted eyeglasses like Mama’s, women in khaki shorts and tank tops, all women with no shoes on. Barefoot. It’s hot now, the sun in the centre of the sky, and the roof of the building is made of metal.

The girl soldiers tell us to step into the makeshift corridors that separate into rooms resembling fitting closets at a store. The rooms are sealed off with cream-coloured fabric. Inside the room I take my dress off and stand in my white underwear and my pink undershirt. I’m almost naked, and barefoot. Mama takes off her skirt and blouse and is left in tight underwear that is meant to tuck her tummy in, and a see-through bra. She’s almost naked, and barefoot. The girl soldier, I notice, looks like a boy, and I would think she’s a boy if it weren’t for her chest. She runs a black machine over Mama’s body and I feel embarrassed for her,

who’s naked in front of this rough-handed stranger. As though she’d heard my thought, the stranger brings the black machine over to my armpits and runs it all over my body. It feels like a black snake. Then Mama farts a huge silent fart that stinks up the fitting room and forces the soldier to leave for a few seconds.

We giggle and Mama says, ‘Kaffik’, and I give her five.

From the room next to ours we hear a girl soldier yell, ‘Ma zeh?’ and then another woman scream in Arabic. Then our soldier tells us to put our clothes on and goes outside to see what’s going on. I rush my dress on, step outside the small room and see the two soldiers looking at a big gold chain and speaking a language that sounds a lot like Arabic.

‘Eyfo? Where?’

‘Ba Kotex shela! Ken! In her Kotex! Yeah!’

The girl who’d hidden her gold chain in her Kotex stands next to them, her arms crossed over her chest. ‘I don’t have money to pay the tax!’ she tells them in Arabic. Mama comes out of the room and takes my hand.

We go and look for our shoes. They’re in a huge laundry bin in the centre of the bigger room. I ask Mama why they’re there, and she says the soldiers took them and X-ray-ed them to make sure we weren’t hiding anything in them.

‘Like what?’ I ask, dangling the top half of my body over the bin. I find cute flower sandals, brown shoes and pretty red heels, but not my shoes.

‘Like bombs,’ Mama says, inspecting her beige heels, ‘and grenades.’

‘But,’ I say, finding one shoe but not the other, ‘I thought grenades were bigger than a … shoe!’ At last I find the other one.

‘Hhhhm!’ exhales a woman in jeans and skinny glasses. ‘The girl’s got more sense than those blind ones!’

A few minutes later the entire bin is emptied, yet the woman in the jeans and the skinny glasses still hasn’t found her shoes.

‘You stole them!’ she says, pointing at a pretty girl soldier with braces on her teeth. The soldier laughs. ‘You bitch! You can’t take my shoes, you hear me? Walek, they’re mine!’

‘I didn’t take your dirty shoes. Now get back in line and get out.’

‘Who took them then? I put them in your goddamn bin and now, poof!’ she clicks her fingers. ‘Gone! Where are they?’

‘Only Hashem knows, lady! Now get in line!’

‘Bala hashem bala khara! Don’t give me that God shit! I want my shoes!’

‘Take them!’ the soldier screams, hurling the strappy sandals at her.

The girl lifts up her glasses and examines the heels. Apparently satisfied, she slips them on and, once outside, says, ‘First my land, now my Guccis! God damn it.’

We sit on a bench in the bright sun and search for Baba. In a little while he reappears and walks over to us with a bottle of water. I want to tell him stories about what just happened, but he says we have to be quiet in case they call our name so we can collect our bags and go. Mama hands me some cookies, which I inhale while black flies buzz around my face and eyes. All around us there are people, people hungry and tired, people waiting. Mama tries to talk to a woman next to her, but Mama’s Palestinian dialect is shabby, and the woman is a peasant. Mama tries the Egyptian dialect, and another woman tells her to keep talking ‘like a movie star’. Mama is embarrassed and stops talking altogether, which suits Baba just fine.

When the sun is half way down in the sky, a soldier yells out our name and Baba crosses the yard and gets our bags from him. We then look for a taxi to take us to Baba’s village, Jenin, and find a van full of people who are going there too. I sit on Mama’s lap this time, and Baba takes my sleeping brother. I watch the ponies as we drive by, the olive trees, the almond trees. I notice how neat the rows of trees are, small sprinklers shooting water at them, the green army jeeps that zoom past us, Baba’s face looking like the sliced rocks in the mountains on our left. I’m so tired; I close my eyes, smell the lemony air, and bury my head in his shirt.

***

Sitto and I sit in the kitchen in the house that my Baba built her and roll cabbage leaves with rice and meat and cumin and salt inside. Sitto looks like Baba, exactly like my Baba, except her hair is longer and she doesn’t scratch her omelets because she doesn’t have any. Her kitchen smells like farts because boiled cabbage releases the farts entrapped within the leaves by evil gassy trolls that comb the countryside. Sitto tells me the story about the two sisters, one poor and one rich. The poor one goes to the rich one’s house and the rich one’s stuffing cabbage leaves. The poor one craves some but the rich one’s a bitch and doesn’t offer her any, so she goes home and makes her own. The mayor comes to visit the poor one’s house for some reason, so she offers him cabbage and he accepts, but while she’s serving it she farts. She turns red and slaps her cheeks and wishes the earth would open up and swallow her, and it does. Underneath the earth she sees a nice town, people and carriages. She walks and bemoans her fate out loud. Suddenly she sees her fart sitting at a café drinking coffee and dressed very posh. She tells him he’s a bastard and why did he embarrass her so? He says he felt stuck inside her and wanted out. The people of the underground town harass him and tell him he needs to make it up to her, so he says, fine, every time you open your mouth gold will drip from it. She goes back up and the mayor is gone and her husband asks, where have you been wife? And she starts to explain but gold drips out of her mouth, and she becomes rich, and never wants for a thing again! And her rich bitch sister, she gets jealous and wants even more riches, so she emulates her sister and farts in front of the mayor when she has him over for stuffed cabbage and the earth swallows her up and she looks for her fart but everyone’s a bum in her underworld, everyone’s sad and impoverished, and when she finally finds her fart he starts cursing her and saying he felt so warm inside her why did she push him out? But she doesn’t get it and she asks him for gold and he tells her to get lost, the villagers expel her and she goes back to her world where the mayor is gone and the husband yells where were you no good wife? And she opens her mouth to explain but scorpions drop out of it and bite her all over until she dies. By the end of the tale all the cabbage rolls are stacked in the pot and Sitto puts the pot on the flame and says, ‘w-hay ihkayti haket-ha, w’aleki ramet-ha And that’s my tale, girl, I’ve told it, and to you, girl, I’ve thrown it.’

I wonder if I love Sitto because of her hikayyat khuraifiyeh, her tales. She tells me to remember the tales, and even though there are a lot of them – one about half a pomegranate, one about a girl who loses her slipper, one about a man with two wives – I do. She tells me that like her grandmother told her the tales and she tells them to me, I must one day tell my kids the tales when they visit me from afar. I want to tell the tales to everyone, and I wish I won’t ever have to have kids, but I don’t dare tell her that.

Back home, in Kuwait, when Baba got letters from his now-dead father, they would include a message from Sitto. My grandpa Sido would write the message for her, and her signature would be a little circle with her name inside it, because she can’t write. Baba explained to me that she used a ring. I never understood this, and thought the ring was the same as her wedding ring. But now, while we wait for the cabbage to cook, she asks me to write her daughter’s husband a letter about the white cheese crop. She dictates it to me. When I give her the paper so she can ‘sign’ it, she takes out her signing ring; it is not her wedding band at all. She dips it in ink and then smashes it onto the paper dramatically, winking at me. It occurs to me that Sitto doesn’t care that she can’t write, because she tells tales and winks and makes cheese.

In the afternoons of the forty-day funeral, for which we will only stay for three days, the women sit in a circle and tell stories about Sido, once in a while slapping their cheeks and rending their dresses. I slap my cheeks and try to rip my dress but Mama shoots me laser-looks and I stop. I just want to be like everyone else.

When I’m alone with Sitto again, I ask her how she met Sido. She laughs and laughs, even though I don’t think my question is funny.

‘You’re pretty, Sitto!’

‘God send away the devil! You liar!’ she pinches my cheek, hard. ‘Your great-grandfather sent your grandfather to come ask after me. He wanted to know if I was available for marriage. But when I saw grandfather, I wanted to be his wife. Like that, I don’t know why. He was very handsome in those days too, and not bald! Your grandfather asked if I was available for marriage, and I answered, yes, I am available to marry him. And I winked! Your grandfather understood, and forgot all about his father. He took me for himself. And after I gave birth to six girls, your father, God keep him, arrived!’

I like sneaking over to Sitto so she can tell me more stories. The day before we leave she tells me about the half-a-half boy who was half a human because his father ate half the pomegranate he was supposed to give his infertile wife to help her carry his child. I wonder if she tells me this because she thinks I’m half a girl since I’m only half-Palestinian. But Sitto must have Mama’s gift, because, as though she’d read my mind, she tells me that the boy in the story is stronger and better than the kids that come from the whole pomegranate, and when she calls me ‘a half-and-half one’, that’s what she thinks of me.

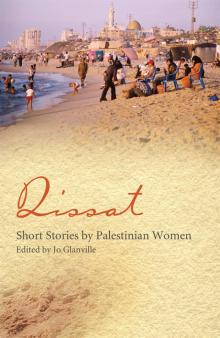

Qissat

Qissat